Designing for Trust: Consumer-Friendly Choice Architecture in Insurance

Insurance is complex

The inherent complexity of insurance products makes it difficult for consumers to understand their differences, features, and associated risks. Trust in financial and insurance services remains low compared to other markets, with consumers often perceiving insurance as a "necessary evil."

Traditionally, disclosures have been viewed as a tool to address complexity and build trust, operating on the premise that correcting information asymmetries enables consumers to make optimal choices.[1] However, this assumption overlooks the challenges consumers face when navigating inherently complex insurance products and processes, which disclosures alone cannot resolve.[2]

As a result, regulators and policymakers globally are increasingly focusing on consumer journey design, choice architecture, and behavioral insights. While these insights can and should be leveraged in the interest of consumers, there is a risk that unconscious biases may be deliberately exploited to persuade consumers into purchasing products that do not align with their needs, objectives, or risk profiles.

Tech policymakers and regulators are particularly concerned about misleading practices that exploit consumer cognitive biases, often referred to as "dark patterns." These practices, common in online insurance and pension user interfaces, steer, deceive, coerce, or manipulate consumers into making choices that are often not in their best interest.[3]

What is online choice architecture, and why does it matter in insurance?

Choice architecture refers to the environment in which users make decisions, including how choices are presented, the design of user interfaces (e.g., websites, online platforms, and mobile apps), and the placement of options.

This architecture can influence consumer decisions in various ways, such as:

Number of choices presented: For example, the number of insurance products displayed on a comparison site or an online broker app, or the range of investment options in IBIPs or pension products.

Description of attributes: Including details like cost, fees, insurance coverage, exclusions, or cancellation steps.

Default options: For instance, pre-selected basic PEPP plans or add-on travel insurance in travel aggregators.

A well-designed choice environment can help consumers make informed decisions, ultimately leading to suitable product selections and reducing protection gaps.

However, poorly designed environments can obscure critical information, set defaults misaligned with consumer preferences, or exploit attention biases to highlight less optimal choices.

Online environments amplify these issues. Research shows that people often behave differently online—acting more quickly, scanning rather than reading, and relying on recommendations from strangers.[4] Think about “finfluencers” here.[5]

This creates opportunities for both helpful and harmful practices. For example, digital interfaces may lower comprehension compared to paper-based information, making certain biases easier to exploit.[6]

Examples of dark patterns in insurance: practices that exploit consumer biases

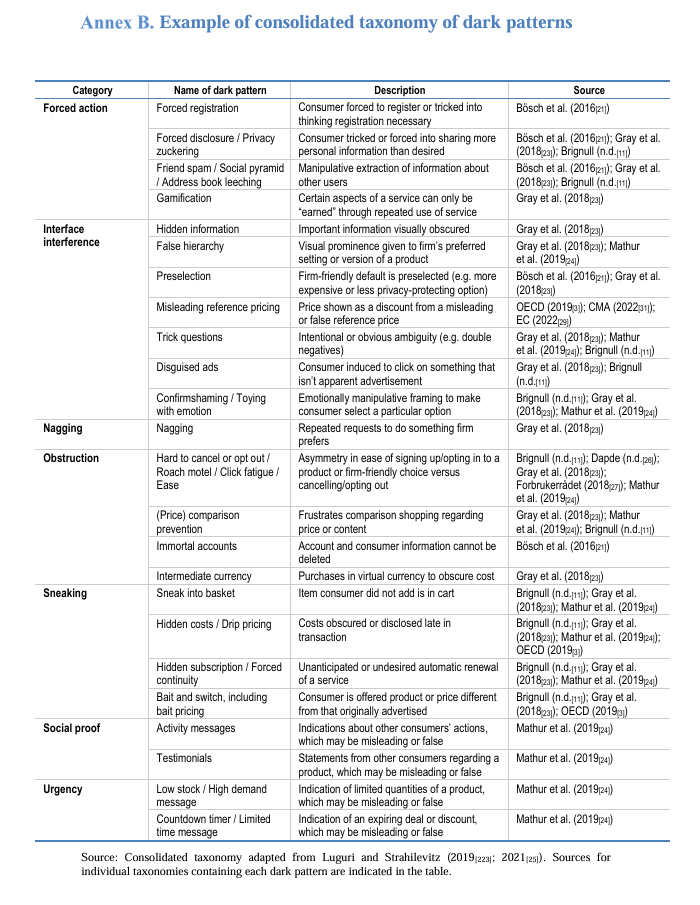

The list of potential dark patterns is extensive. The OECD recently proposed a taxonomy of these practices.

EIOPA has also highlighted several misleading techniques observed on European insurers' websites.[7]

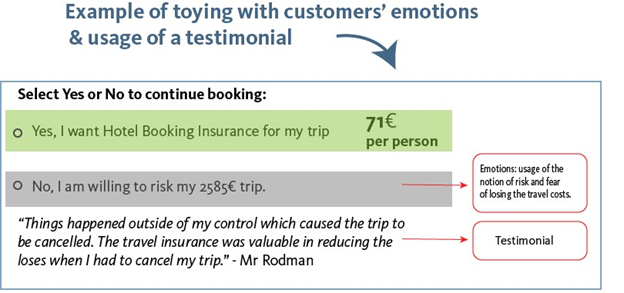

These include:

· Social proof

· Toying with emotions

· Hidden information

· Prize contests

· Sense of urgency

· Forced action

· Pre-selected options

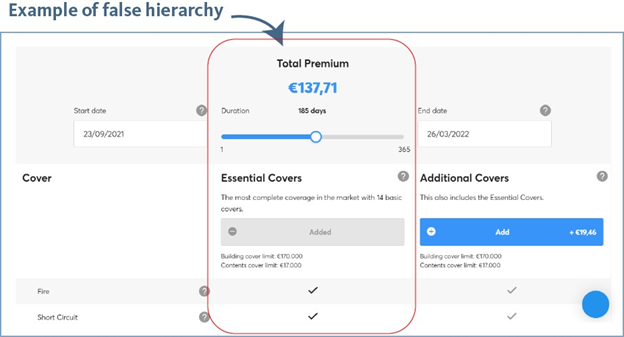

· False hierarchy

Potential toolbox for insurance regulators and supervisors

From a regulatory perspective, behavioral insights and consumer journey design principles should prioritize consumer interests. However, these principles can also be misused to manipulate consumers. Addressing these risks requires a robust approach from regulators and policymakers.

A theoretical regulatory toolbox could include:

· High-level consumer journey design principles, such as prohibiting dark patterns or mandating consumer-friendly purchase flows.

· Consumer testing and greater integration of these issues into product design and development.

· Monitoring and enforcement to ensure firms act in consumers' best interests.

In its advice to the European Commission, EIOPA has in past emphasized the need for future-proof regulations addressing the impact of choice architecture on consumer decisions. The advice proposed measures to ensure firms use behavioral insights ethically, particularly in digital contexts. This includes designing choice environments that nudge consumers toward sensible decisions and suitable products for the right target markets.[8]

The advice also suggested requiring firms to adopt policies and tools that prioritize consumers' best interests, regularly review these tools, and ensure compliance with existing principles under the Insurance Distribution Directive (IDD). Firms should use behavioral nudges and gamification techniques only if they align with consumer interests and avoid potential harm.

Recent developments and future directions

The European Commission has already taken concrete steps, such as proposing new rules on online fairness. As part of the Distance Marketing Review[9], a provision was added to the Consumer Rights Directive[10] requiring Member States to ensure that traders, when concluding financial services contracts at a distance, do not design, organize, or operate their online interfaces in a way that deceives or manipulates consumers.

This includes avoiding practices that materially distort or impair consumers' ability to make free and informed decisions.

Furthermore, the European Commission has recently published the Report on the Digital Fairness Fitness Check[11], which is expected to significantly influence the future of digital consumer protection in Europe, including in sectors such as insurance and financial services.

The report identified several problematic practices that hinder consumers' ability to control their online experience, including:

- Dark patterns: Online interfaces that unfairly influence consumer decisions, such as using false urgency claims to pressure users.

- Addictive designs: Features in digital services that encourage excessive use or spending, such as gambling-like elements in video games.

- Personalized targeting: Advertising that exploits consumer vulnerabilities, such as financial challenges or negative mental states.

- Challenges in managing digital subscriptions: Companies making it excessively difficult for consumers to unsubscribe.

- Problematic commercial practices by social media influencers: Deceptive or unethical marketing techniques.

Ursula von der Leyen has already tasked the next Commissioner for consumer protection with developing a Digital Fairness Act. This legislation aims to address unethical practices, including dark patterns, influencer marketing, addictive design features, and online profiling, particularly when consumer vulnerabilities are exploited for commercial gain.[12]

As a result, digital fairness will be a priority for the next Commission, with the proposed legislation likely building on the findings of the Digital Fairness Fitness Check report.

To conclude, while innovation should be encouraged, it is crucial to uphold a robust consumer protection framework. Further research is needed to better understand harmful market practices, design effective regulatory tools, and ensure a balanced approach that protects consumers while fostering innovation.

[1] See ‘ ASIC and AFM (2019), “Disclosure: Why it shouldn’t be the default, A joint report from the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM)” https://download.asic.gov.au/media/5303322/rep632-published-14-october-2019.pdf

[2] Op cit, page 8. See also Moutinho, Ana Teresa and Lehtmets, Andres (2023, January 1). Pan-European regimes: A pathway to mitigate lack of trust and complexity in insurance. In the Journal of Financial Compliance, Volume 6, Issue 2. https://doi.org/10.69554/CFGF9070

[3] See in general OECD (2022), "Dark commercial patterns", OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 336, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/44f5e846-en.

[4] Online Choice Architecture: How digital design can harm competition and consumers, Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), 2022. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1066524/Online_choice_architecture_discussion_paper.pdf

[5] An influencer who gives advice on financial investments.

[6] For example, websites often pre-select or highlight in green their preferred selection, e.g. “accept all”.

[7] Dark patterns in insurance: practices that exploit consumer biases https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/dark-patterns-insurance-practices-exploit-consumer-biases_en

[8] See EIOPA Technical advice on Retail Investor Protection (2022) https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/advice/final_report_-_technical_advice_on_retail_investor_protection.pdf See also Joint ESAs Report on Digital Finance (2022) https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/document-library/report/joint-esas-report-digital-finance_en

[9] Distance marketing of financial services - European Commission

[10] Directive - EU - 2023/2673 - EN - EUR-Lex

[11] Study to support the fitness check of EU consumer law on digital fairness and report on the application of the Modernisation Directive - European Commission

[12] See Mission Letter to Commissioner-designate for Democracy, Justice, and the Rule of Law 907fd6b6-0474-47d7-99da-47007ca30d02_en

Member discussion